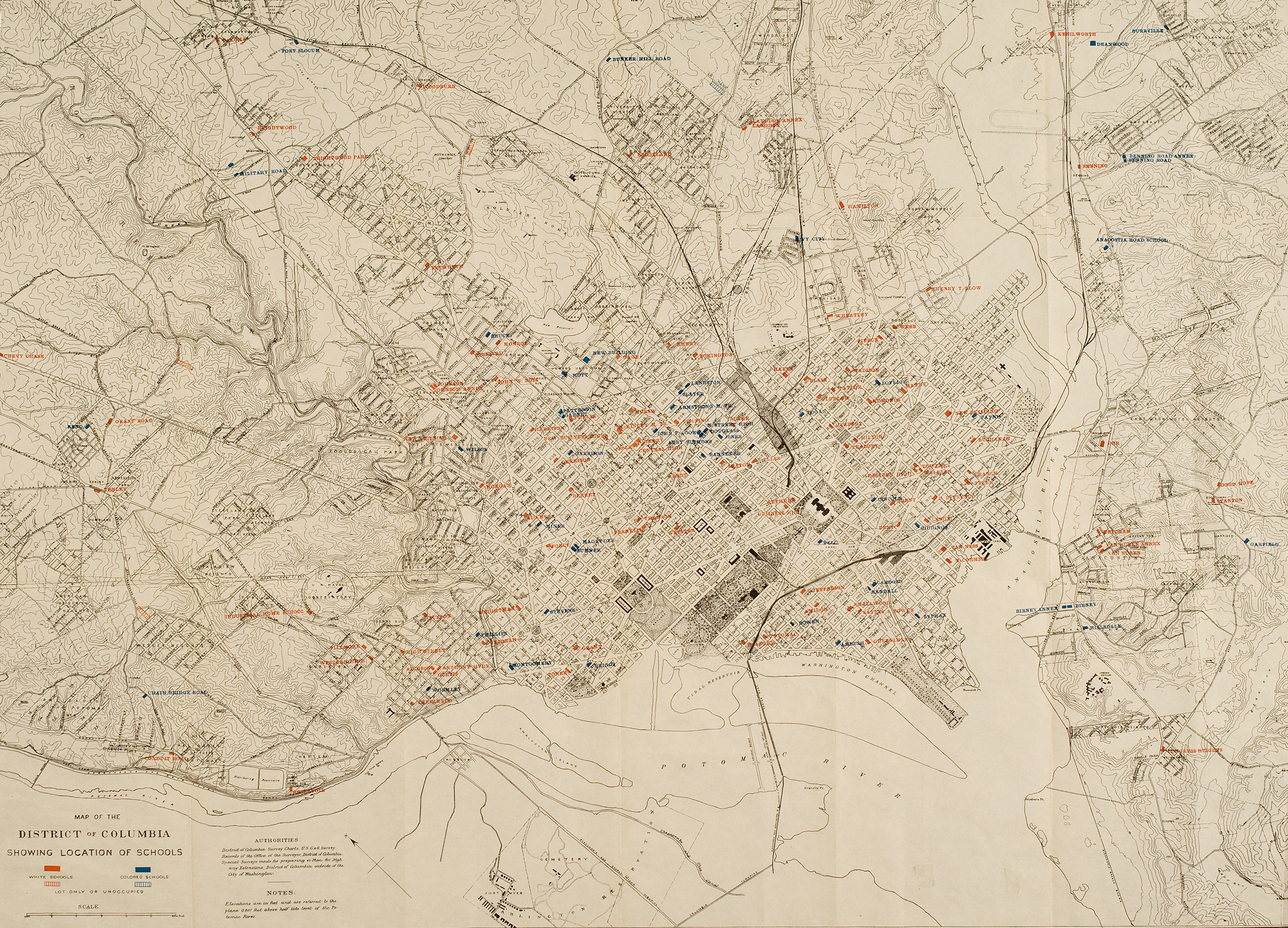

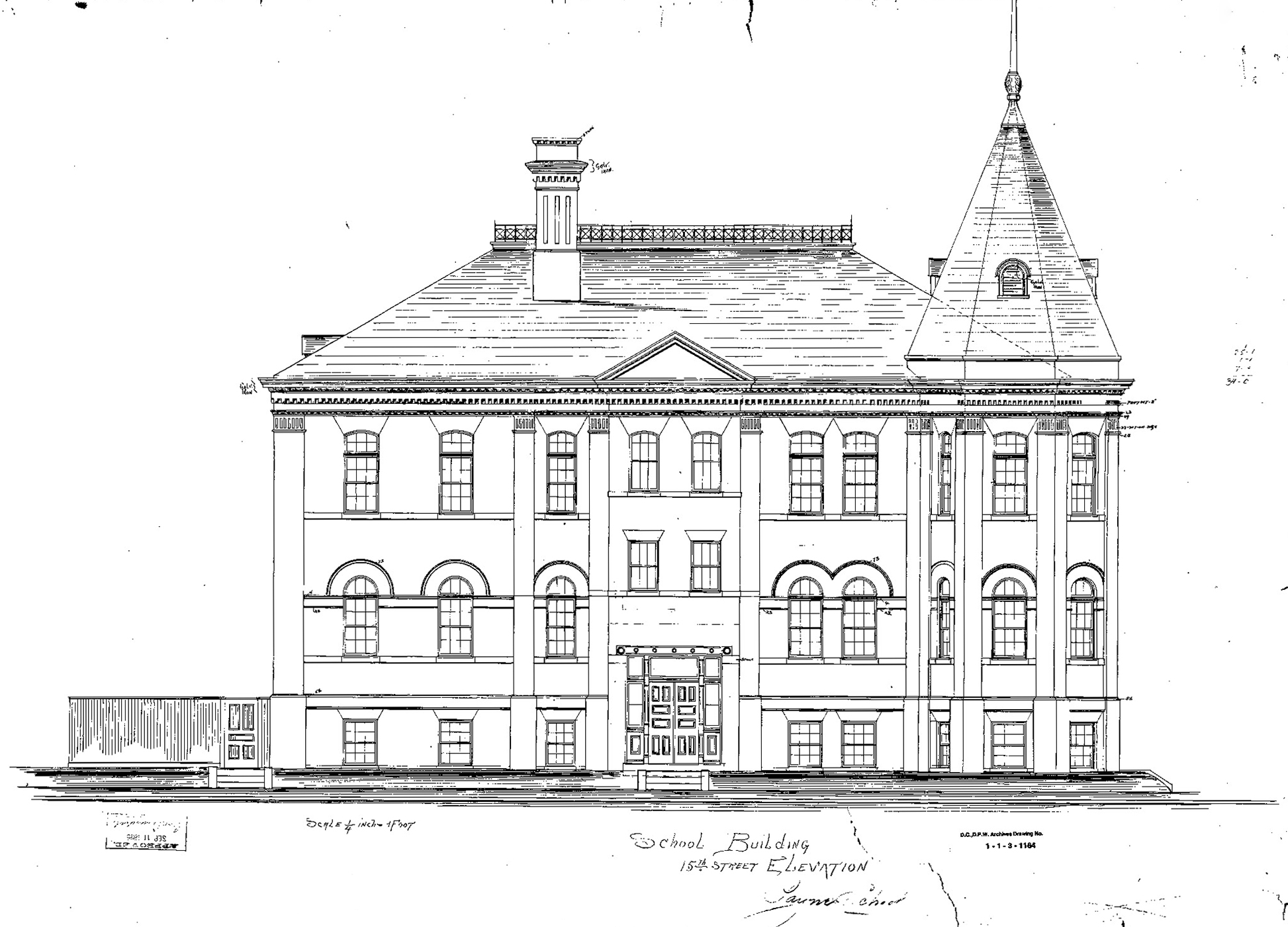

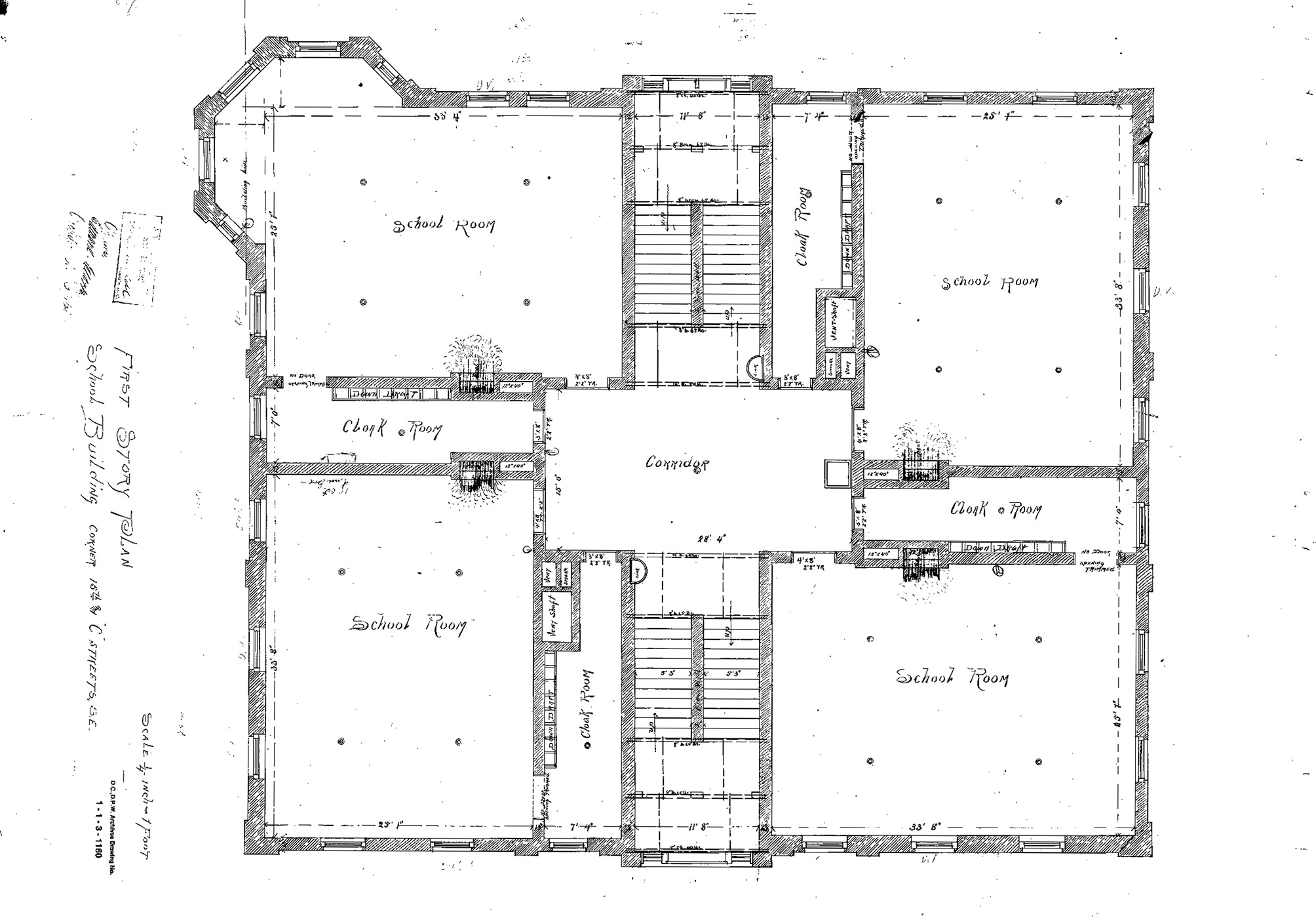

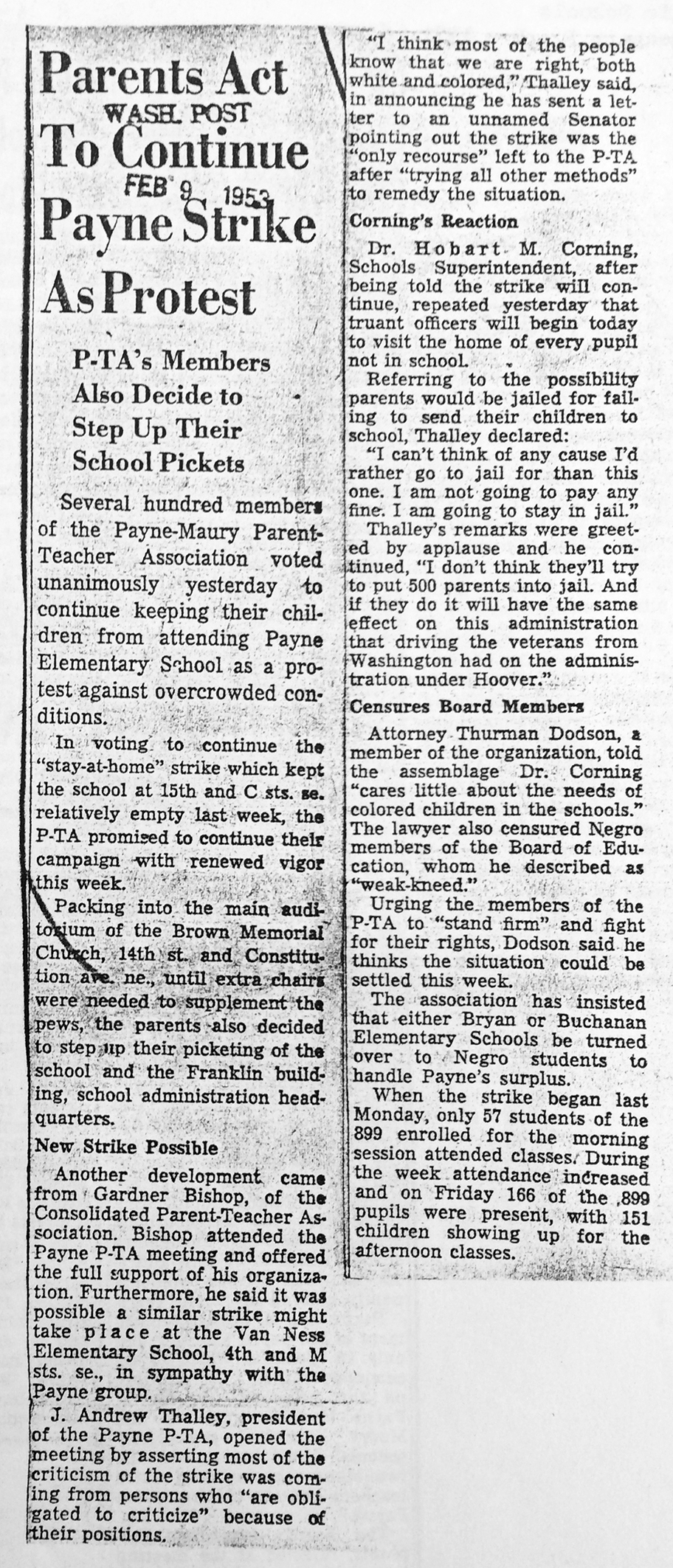

The original Payne Elementary School was built in 1896 to serve African American students. At that time, Washington, DC schools were segregated by race. As the city grew, many of the black schools became overcrowded and fell into disrepair, while nearby white schools were renovated and operated under capacity.

In the late 1940s, parents of Payne Elementary students joined other working class African American parents living east of the Anacostia River to speak out about the deplorable conditions of their aging schools. They led a series of protests, during which they kept their children home from school. Their activism contributed to the landmark 1954 court case Bolling vs Sharpe that ended DC school segregation.

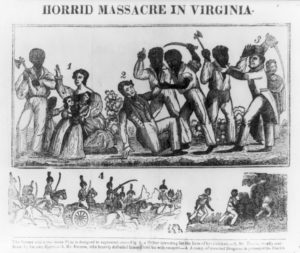

Nat Turner leads his fellow slaves in a revolt in Southampton County, Virginia. In August 1831, Turner and his rebels kill nearly 60 people, most of whom are white slave owners. The rebels free the slaves. Nat Turner is eventually caught and executed.

Nat Turner leads his fellow slaves in a revolt in Southampton County, Virginia. In August 1831, Turner and his rebels kill nearly 60 people, most of whom are white slave owners. The rebels free the slaves. Nat Turner is eventually caught and executed. Daniel A. Payne is ordained the first black minister in the Lutheran Church in Fordsboro, New York. A few years later, he leaves the Lutheran Church and joins the African Methodist Episcopal.

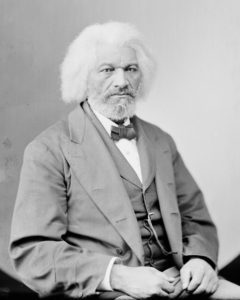

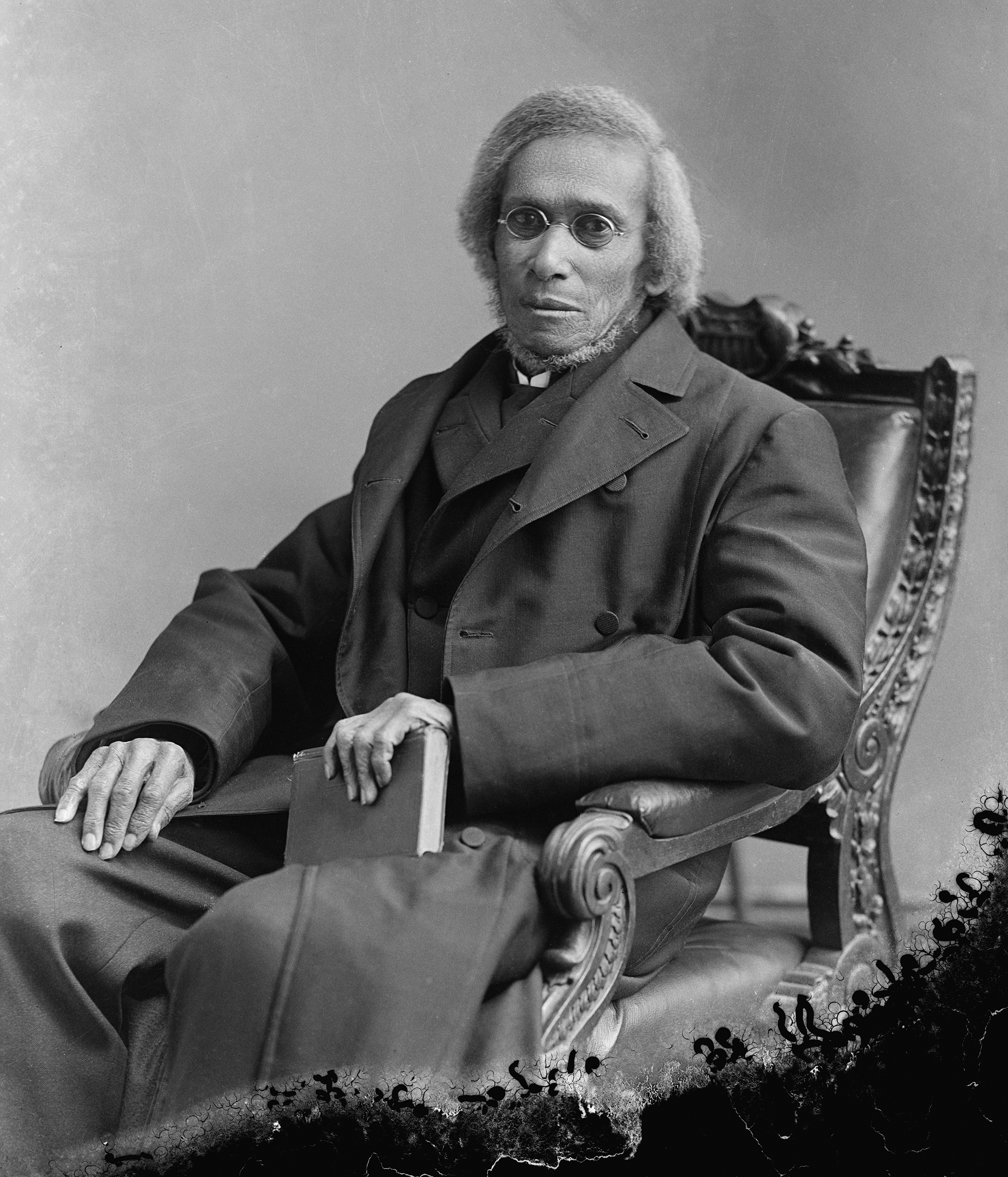

Daniel A. Payne is ordained the first black minister in the Lutheran Church in Fordsboro, New York. A few years later, he leaves the Lutheran Church and joins the African Methodist Episcopal.

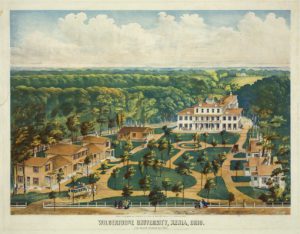

Bishop Daniel Alexander Payne dies in Xenia, Ohio on November 2, 1893. He is buried in Laurel Cemetery in Johnsville, Maryland.

Bishop Daniel Alexander Payne dies in Xenia, Ohio on November 2, 1893. He is buried in Laurel Cemetery in Johnsville, Maryland.