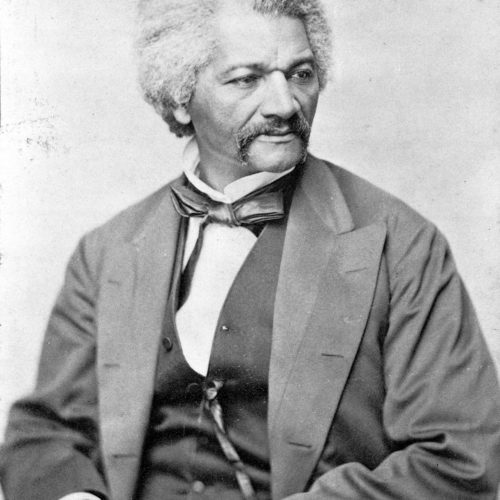

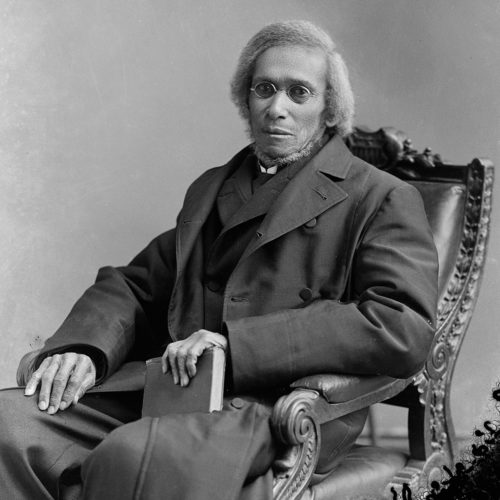

Before the 1860s, there was little public education available in the District of Columbia, and what was available was offered to white students only. This changed after April 16, 1862, when President Abraham Lincoln signed the District of Columbia Compensated Emancipation Act, freeing the enslaved people in D.C. Encouraged by leaders such as Daniel Payne, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Jacobs, Black Washingtonians pushed for educational opportunities for their children. A new segregated public school system was the result. Even though resources were scarce, by 1864 D.C. was educating close to 5,000 Black students.

The Exhibit

"100 Years of Our School's History"

A New School System

Pushback

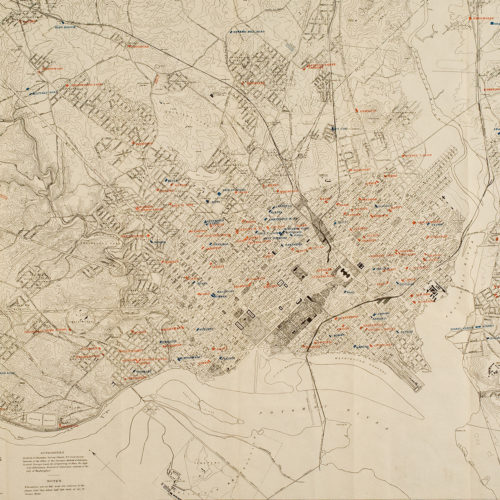

Washington, D.C. became a national leader of racial change. During the decade following the American Civil War, Black men saw new freedoms as the city’s progressive anti-discrimination laws produced job opportunities and the right to vote. The Black population increased significantly between 1870 and 1880 as more families moved from the south into the city. However, even with earnest efforts for racial equality, a few decades later D.C. would see a surge in white backlash as city commissioners began to quietly drop anti-discrimination laws in favor of strict racial segregation.

In the early 1900s, D.C. public schools were arranged in divisions determined by geographical boundaries. The schools in divisions 1 – 6 educated white students, divisions 7 – 8 consisted of Black and white schools, and divisions 9 – 11 educated Black students. Division lines were redrawn in 1906 to follow new geographical guidelines. Schools in nine divisions (1 – 9) educated white students; schools in only 4 divisions (10 – 13) educated Black students. Most white schools had vacancies while most Black schools exceeded capacity.

Hine Junior High School

In 1923, white families residing in the area that is now Capitol Hill began sending their children to the new Hine Junior High School. Hine’s 1892 building, located near Eastern Market, had originally housed Eastern High School. Both Eastern and Hine educated only white students.

As the population grew, the school expanded. Towers Elementary, built in 1887 and next door to Hine Junior High School, was converted into an annex for Hine.

During this time, most of the schools that educated Black students were located in Northwest, D.C. There were no junior high schools for Black families on the east side of the city.

Community Voices

”…you went to Towers first…[then] you went to Wallach. When you got through at Wallach you went to Hine…it had gotten so old that when you went up the steps they scooped...all those little footsteps going up and down…

Mary JerrellOverbeck Oral History Project, 2003 interview

Who was Lemon Galphin Hine?

Lemon Galphin Hine was born on April 14, 1832, in Ohio. At the age of 19, he became the manager of a Cleveland newspaper. He then studied law in New York. In 1860, he married Mary Tillinghast and together they had 5 children.

Hine enlisted in the Union Army during the Civil War, rising to the rank of Lieutenant. After losing his voice as a result of an injury, he left the army and moved his family to Washington, D.C., where he practiced law. From 1869 to 1883, he conducted more than one-sixth of all D.C.’s civil cases.

In 1868, he entered D.C. politics and was elected to the city council. From 1870 to 1871, he served in the legislative branch of the local government. Problems with his throat continued to plague him. In 1883 he stopped taking new cases and in 1887, retired from practicing law.

He returned to civic service in 1889 when President Benjamin Harrison appointed him to the three-man team that governed D.C. During this time he also invested in new inventions, including a typesetting machine which preceded the printing press.

After spending 50 years in D.C., he died in Michigan on January 19, 1914. His obituary stated, “He was a man of the highest character and greatly beloved by all who were privileged to know him.”

Eliot, Hine, and Browne Junior High Schools

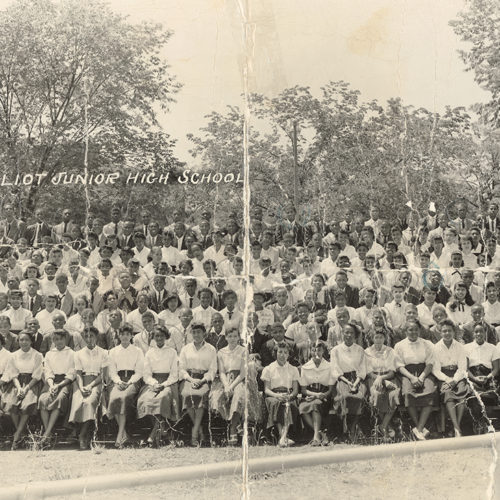

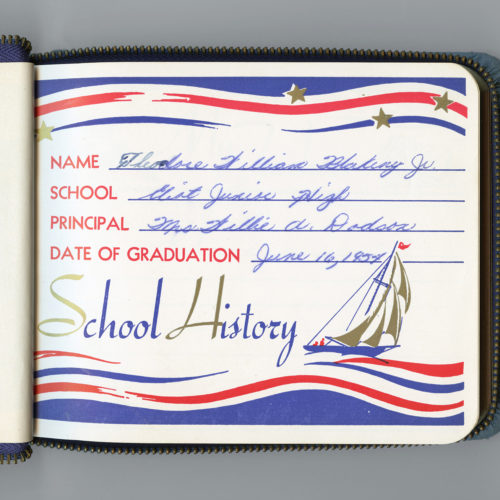

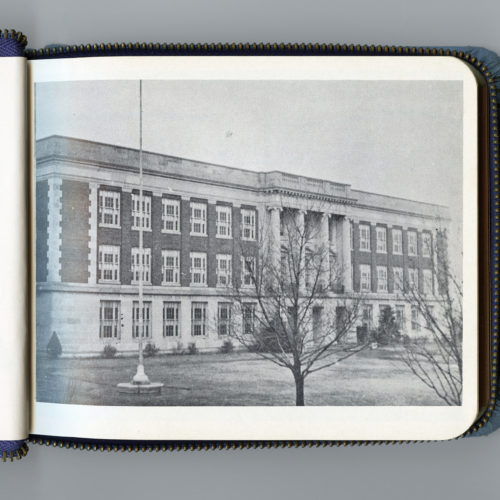

In 1931, a second junior high school for white students, Eliot Junior High School, was built at 18th and Constitution Avenue NE. Even with this new school, Hine Junior High School needed more space and an annex was built in 1932 to join the two separate Hine buildings. In 1936, Eliot also received a new addition.

In 1932, a junior high school for Black students was finally built in Northeast D.C. When it opened, Hugh M. Browne Junior High School enrolled 888 students, its maximum capacity. Within the next few years, the student body almost doubled.

Who was Charles Eliot?

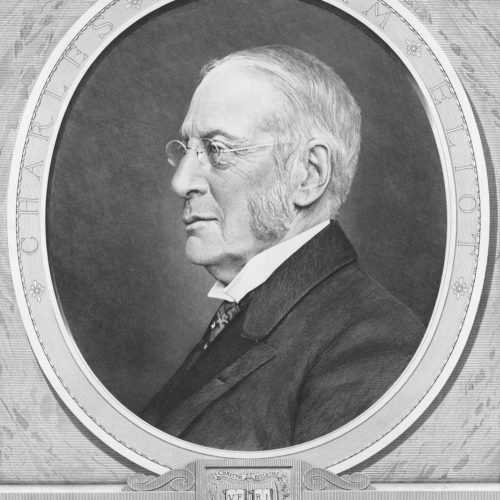

Charles William Eliot was born in Boston on March 20, 1834. He did well academically and enrolled at Harvard University to study science when he was 15. In 1858, he married Ellen Derby Peabody, and they had four sons.

At the age of 35, he became President of Harvard University, where he oversaw development of the elective system that let students pick most of their own classes. He pioneered lecture courses, abolished mandatory religious worship, and instituted 4 year bachelor degrees.

Eliot held some progressive beliefs for his time. Although he did not believe in the education of women, he opposed racial discrimination in universities. While he was President of Harvard, Black students, including W.E.B. Du Bois, were admitted and received degrees. Booker T. Washington received an honorary degree.

In 1909 Eliot retired and toured the south as an education ambassador. Newspapers reported that during his seven-week trip, his speeches contained controversial, racially-charged remarks.

He died on August 22, 1926, in Maine. His obituary stated, “He labored to unify the entire educational system, cast off monotony and introduced freedom and enthusiasm.”

Overcrowding, Changing Enrollments, and Deteriorating Schools

In the 1940s, Browne Junior High School remained the only junior high school in Capitol Hill that educated Black students, but two new Black junior high schools, Kelly Miller and Douglass, opened east of the Anacostia River. In November 1947, Browne Junior High School had an enrollment of 1,826 students even though the building’s capacity was only 888.

Between 1935 and 1947 the number of students at Eliot Junior High School dropped by 15%. Being more than half a century old, Hine’s buildings were deteriorating and creating unsafe conditions for its students.

Community Voices

”The 61-year-old Hine Junior High School, which school officials want to replace with a modern building, is a hodgepodge structure composed of an old high school and an old elementary school joined by two comparatively new sections…

Coit Handley Jr.Journalist, 1948

The Right to an Equitable Education

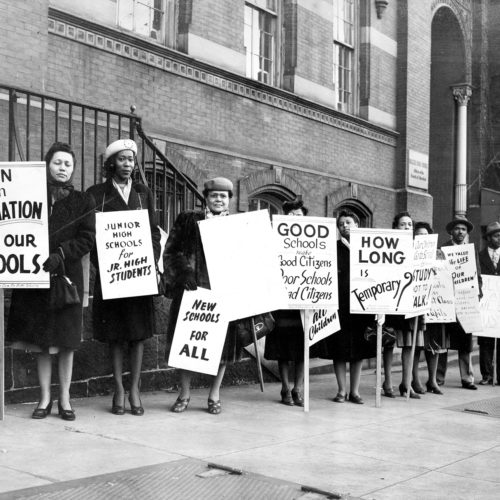

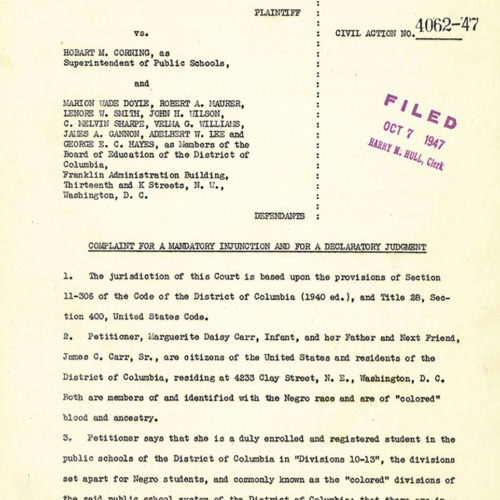

In the fall of 1946, Marguerite Daisy Carr attended Browne Junior High School. Enrollment at the school was so high that each student could attend only one of two 4.5 hour sessions. To give Carr the standard 6-hour day, her parents tried to transfer her to Eliot Junior High School. Their request was denied on the grounds of race — Carr was a Black student and Eliot was a white school.

On October 7, 1947, Carr vs. Corning was filed on behalf of her and all others in a similar situation, alleging that they were being denied the full benefits of a free education. In November and December, the Board of Education began eliminating Browne’s double shift by moving students to vacant elementary school buildings.

In January 1948, the Browne Parent-Teacher Association brought a class action suit claiming that the elementary school buildings lacked the facilities and equipment suitable for junior high schools. This case was dismissed. Even with the use of the elementary school buildings and the two Black junior high schools across the river, the student population of Browne still exceeded capacity.

School Integration

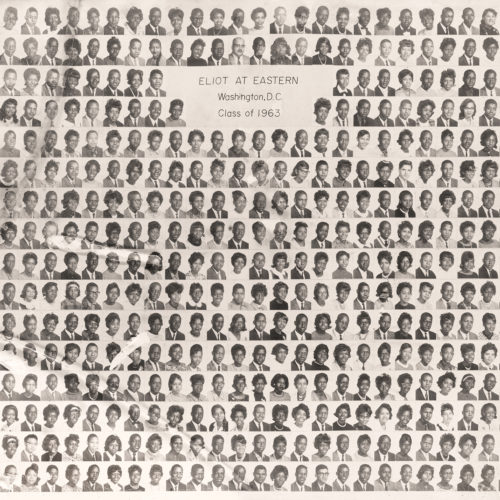

In 1952, the Board of Education transferred the white students from the half-occupied Eliot Junior High School to Eastern High School, creating a new Eastern Junior-Senior High School. Eliot reopened to Black students in an attempt to eliminate overcrowding at Browne.

As parent advocacy groups grew, out-spoken community leaders and lawyers began to fight for an integrated school system. In 1950, Spottswood Bolling and 11 other students were denied admittance to the newly-built John Philip Sousa Junior High School on the basis of race. Bolling would become the plaintiff in the Supreme Court case Bolling vs. Sharpe, which in 1954 mandated integration of the D.C. public schools.

After integration, white families began to leave the city. By the end of the decade almost all Capitol Hill’s public school students were Black.

Community Voices

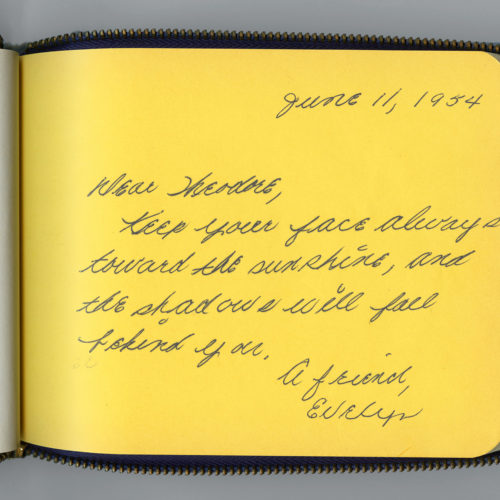

”The population [of D.C.] was mostly Black by the time we got to Eliot. There were white kids with us in elementary school but by 1960, they had mostly moved to the suburbs…We had mostly Black teachers. The city was changing fast.

John GarnerEliot student 1958-1960

”I attended Eliot Junior High School from September 1952 - June 1955…we had to commute on the street car…the whole neighborhood was racist…they did not want Blacks at Eliot, mind you this was 1952 two years before integration.

Medell FordEliot Class of 1955

”I was a graduating ninth grader when the court announced the [Brown vs. Board of Education] decision. I remember Mr. Gardner Bishop…was on the front page of one of the local newspapers with an African American student named Spottswood Bolling…He became my roommate in college.

Ted BlakeneyEliot Class of 1954

”During integration Eliot was still mostly all Black. I can’t remember seeing white folks in there…[Mr. Jameson] helped me out a lot, he encouraged me. I always loved going to school.

Gerald R. AndersonEliot student 1956-1957

”In fact, there weren’t that many Black kids who came [to Hine] right away…As I recall, it was more like just a few came in.

Elias SouriOverbeck Oral History Project, 2002 interview

”My parents moved our family from Charlotte, NC in July 1951...I attended Browne Jr. High in the 7th grade and it was like a prison. We stayed in school all day every day...I attended Eliot Junior High in the first year it opened. I was in the 8th grade...it was great. We could go outside for recess.

Ted BlakeneyEliot Class of 1954

Hine Rebuilds, Eliot Expands

In the 1960s, the three buildings that composed Hine Junior High School had deteriorated to the point that they had to be demolished. In 1966, a new Hine Junior High School was rebuilt on 7th Street SE just north of Pennsylvania Ave SE, across from Eastern Market.

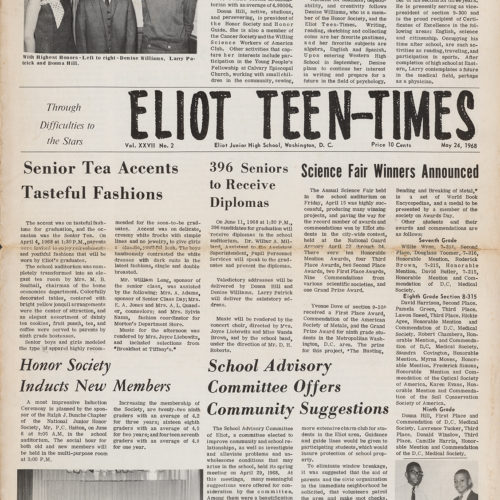

Eliot Junior High School thrived. Eliot had a strong business preparatory program. Competition in academics and athletics was stressed. A strict dress code was enforced, requiring young men to wear ties. The diverse curriculum included field trips, art, gym, orchestra, band, singing, woodworking, printing, and personal family living. As more students enrolled, the building was expanded. However, the renovations presented operational challenges and problems with misaligned levels.

Community Voices

”[My fondest memory was] learning to use my hands in creating art and wood carvings…The male teachers would always tell us that if we are successful, they as teachers will be successful.

James WesleyEliot Class of 1963

”I lived four blocks from Eliot… Everyone in the neighborhood went to Eliot so we were just like a family. My typing class helped me to become an exceptional secretary.

Brenda WayneEliot student 1962-1964

”There were two corner stores on the way to [Eliot]...On the block in between was…the Street Car Barn…I didn’t think I could ever get used to not hearing the squeak of the street car as it turned the corner at Lincoln Park.

Dawn Bennett-AlexanderEliot Class of 1965

”…My homeroom teacher…was the best man in my life at that time and likely was my inspiration to become a junior high school teacher.

Cynthia McIverEliot Class of 1965

”We had parents who took an interest in their children’s education. We also had prayer and discipline in the schools back then…Most of us wanted to learn and the teachers wanted to teach…they really wanted us to succeed…

Francis PierceEliot Class of 1964

”Excellence was the goal in our class at Eliot, The Little E!

Rodney NewmanEliot Class of 1968

Serving the Community

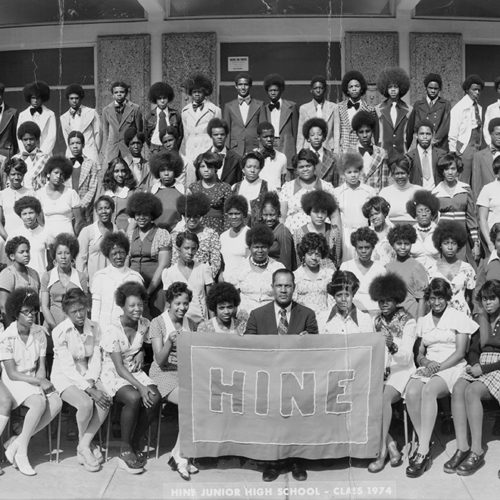

In the 1970s and 1980s, Eliot and Hine Junior High Schools continued to serve their tight-knit Capitol Hill communities and their talented students.

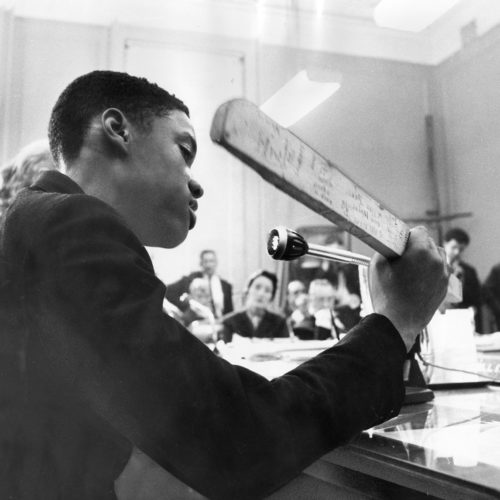

Corporal punishment had long been used as a disciplinary measure in schools. By the 1970s, some people, including students and teachers, began protesting the practice. D.C. Public Schools banned corporal punishment in 1977 after the Supreme Court gave states the power to criminalize its use in schools.

Progressive teachers wanted to expand the curriculum to include works by people of color, such as Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun, as well as use audio recordings from civil rights demonstrations in their classrooms.

As the 1980s came to a close, a crack cocaine epidemic brought a surge in drug use and violence to D.C.

Community Voices

”When the [football] stadium rocked, our houses rocked! Block parties. Playing football in the snow. Helping one another and enjoying one another’s company...We had freedom to travel the city feeling safe. METRO bus drivers let you catch the bus for free with a brief parental lecture on safety…

Rachelle LucasEliot Class of 1984

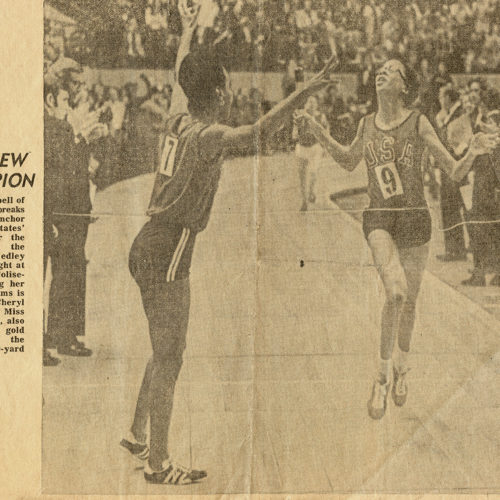

”I made my first USA National Track team at 14 years old while I was a student at Hine. As the anchor leg on the USA National Relay Team my picture appeared on the front page of The Washington Post. I was late to school after my weekend exploits and was embarrassed when everyone clapped and my picture was posted on the board next to my desk.

Robin Campbell-BennettHine Class of 1973 and Olympic track and field athlete

”I used A Raisin in the Sun with great success in one my slowest ninth grade classes. The kids picked it out of the

Susan RuffHine teacher, quoted in The Washington Post, 1967

bookmobile themselves. One boy who was playing one of the roles—a very bad reader—finally got interested enough in something to actually read. I overheard him say, ‘You got to learn to read some god damn time.’ The language wasn’t good, I admit, but it meant he really wanted to learn for the first time in his life.

”Hine was my in-boundary school...That’s where my friends were. The school culture at Hine was one of family. Our classes were very demanding, and our work ethic had to be on point in order to succeed. They promoted that we respect ourselves and others, as well as do our best.

Celine ParkerHine Class of 1987

”During the 1980s and 1990s, the city was engulfed by a drug epidemic and heightened violence—D.C. was known as the ‘Murder Capital of the World.’ There were many lives lost. However, the schools remained a safe space. They provided positive outlets such as music, art, and athletics.

Dr. Sherri BrownEliot student 1988-1990

”My favorite thing about [Eliot Junior High] was how togetherness was practiced…We always felt safe in school.

Keysha LuckeyEliot Class of 1988

”Mr. Rhinehart, my science teacher, made it so easy and engaging to learn science. He helped me understand that we all don’t learn the same but if you stay the course you will get it by repetition…I was eager to learn and discover more about space through his creative way of connecting with youth.

Betty EntzmingerEliot Class of 1973

”The teachers were friendly enough overall but back then some could be pretty strict…they wanted to do their jobs and at that time they would punish some people, especially some boys would regularly be hit with paddles…

Cynthia McIverEliot Class of 1965

Eliot and Hine Merge

During the 1990s and early 2000s, Eliot and Hine Junior High Schools began to see a drop in student enrollment as their buildings continued to age. Under Principal Whitfield’s 13-year leadership, Hine Junior High School won the Blue Ribbon for Excellence from the U.S. Department of Education. The Hine Junior High Panthers’ marching band participated in President Clinton’s 1993 inaugural parade.

In 2008, despite objections from both school communities, Hine Junior High School closed and merged with Eliot Junior High School. Fewer than 35% of Hine 6th and 7th graders stayed in the consolidated school.

The new school community of Eliot-Hine Middle School moved into Eliot’s building on Constitution Ave, NE. The building was almost 80 years old and in desperate need of mechanical and structural repairs. The community pushed D.C. Council to resolve these problems, but it would be more than a decade before the school saw any facility improvements. In 2015, the old Hine Junior High School was razed and replaced with condominiums and a grocery store.

Community Voices

”I saturated [the students] with love. Nothing kept me from getting on the intercom and telling them I loved them. I kissed them. I hugged them.

Hine Principal WhitfieldQuoted in The Washington Post, 1995

”I’m very proud of this school and feel that Hine prepared me to go on to college.

Cherre PriceQuoted in The Washington Times, 1992

Eliot-Hine Middle School

In 2019, Eliot-Hine’s building renovation began. The 1961 addition was replaced by an ADA-accessible facility. Other parts of the building were renovated and restored. The reconfigured interior space created a high performance learning environment including state of the art technology, professional-grade music and art rooms, and new athletic fields and weight rooms. The two-story auditorium was restored to its original style. New landscaping and gathering places highlighted the 1930s entry facade and created a welcoming exterior space. The finished facility met or exceeded LEED-GOLD standards for sustainability.

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic caused unprecedented disruption of public education. D.C. Public School buildings closed and the city issued a stay-at-home order to help slow the spread of the virus. Virtual, at-home learning replaced in-person classes and made obvious the equity differences among students. As the pandemic raged world-wide, families and friends were forced to stay apart as scientists raced to create a vaccine.

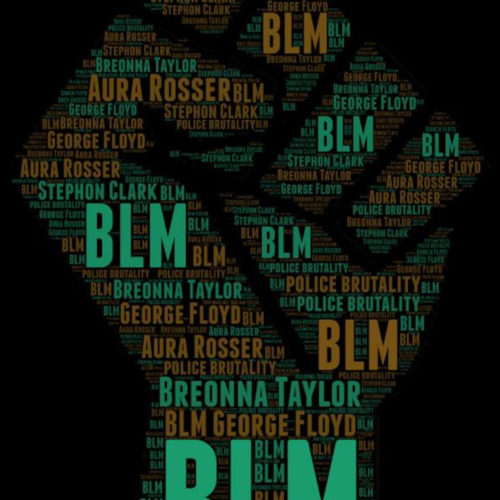

In the midst of the pandemic, the killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis thrust into the spotlight the nationwide police brutality that was continuing to take the lives of innocent Black people. The organization Black Lives Matter exploded into prominence, building local power within Black communities, as Black people and their allies fought systematic racism and white supremacy.

Community Voices

”Black Lives Matter means more than the world to me and my community…A part of me is kind of sad that I can’t live as free as I want because of the color of my skin. As a Black human—that will one day be a man—the movement helps me understand who I am today and who I will become…

Diallo SekouEliot-Hine 7th grader, 2021

”During the [COVID-19] pandemic, I can’t go inside my actual school building and I must stay inside [at home] and use a computer. This makes me miss my friends and teachers. I have to stay inside all the time, and I see my friends over video chat or online. I get to hang out with my family—we play board games, go on really long bike rides, and have dinner together more.

Bailey MasonEliot-Hine 7th grader, 2021

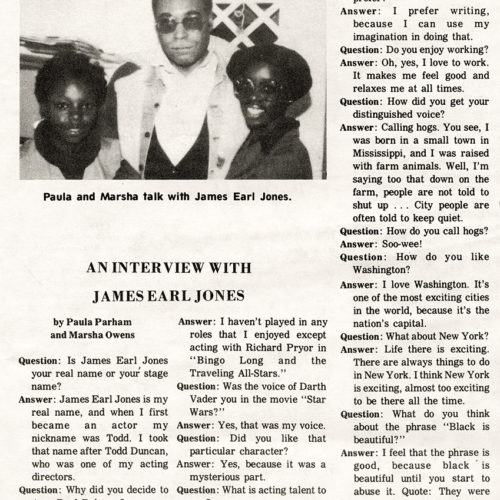

”Having been interviewed by Eliot-Hine Radio…I know that they are a truly special group of young people…These remarkable young people are worthy of our support and encouragement because we need more talented individuals embarking on such careers. After all, as I have said many times before, without the media, the civil rights movement would have been like a bird without wings.

John LewisFrom his letter to The White House, 2013

”At Eliot-Hine we envision a future of globally minded, actively engaged leaders who remain curious and passionately pursue their dreams. Our school has a rich history of activism, and as a community we will undoubtedly continue to take on tough issues and advocate for social justice. This exhibit reveals the powerful legacy of those who came before us and the deep roots from which we will continue to grow as we embark on an ambitious new chapter as a school community.

Marlene MagrinoEliot-Hine Principal, 2021

The Exhibit

The Story of Our Schools would like to thank the following for their generous grants and donations that made this exhibit possible:

District of Columbia Government | Capitol Hill Community Foundation | Alex and Maryam Nock | Penn Hill Group | Danica Petroshius and Greg Whitsell | Cathy Albright | Georgetown Public Affairs | Dave and Janet Hunke | Erin and Brian Roth

Every school has a story to tell.

Are you ready to explore the story of your school?

Contact us to learn more about bringing The Story of Our Schools to your neighborhood or make your tax-deductible contribution today.