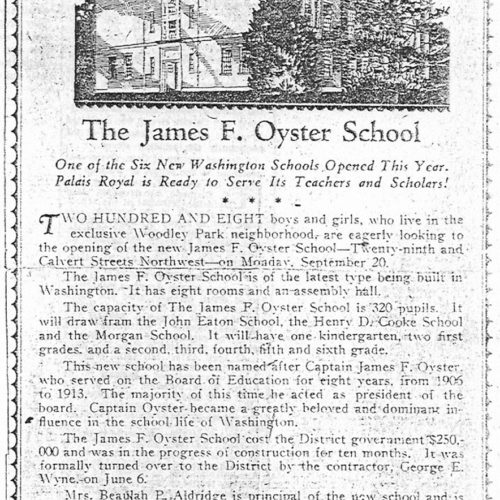

Surrounded by embassies and an affluent neighborhood, a new school opened in Woodley Park in 1926. The school had eight classrooms and an assembly hall to serve 320 white students in kindergarten to sixth grade. All classes were taught in English. It was named for James F. Oyster, a former president of D.C.’s Board of Education. In 1954, racial integration of D.C. public schools brought few changes to Oyster School.

The Exhibit

Las Raíces Bilingües (the Bilingual Roots) de Oyster-Adams

A School for Woodley Park

An Experiment in Bilingual Education for a Changing Community

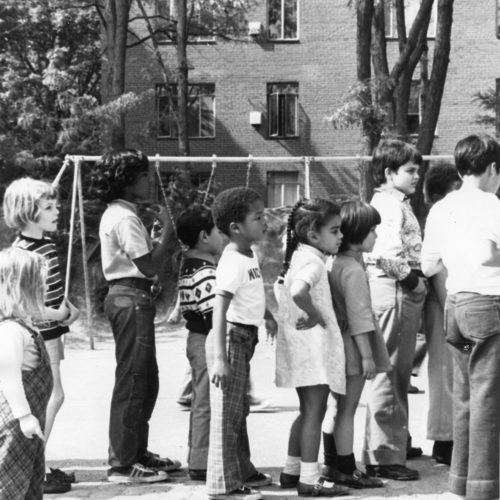

The 1960s and 1970s brought heightened racial tensions across the nation. As the Civil Rights Movement grew, Spanish-speaking families immigrated to the United States and settled in Adams Morgan and Mt. Pleasant. Many took jobs with international organizations or started businesses, bringing their rich culture and traditions into the neighborhood. The Civil War in El Salvador brought many Salvadorans to DC in search of safety and opportunity.

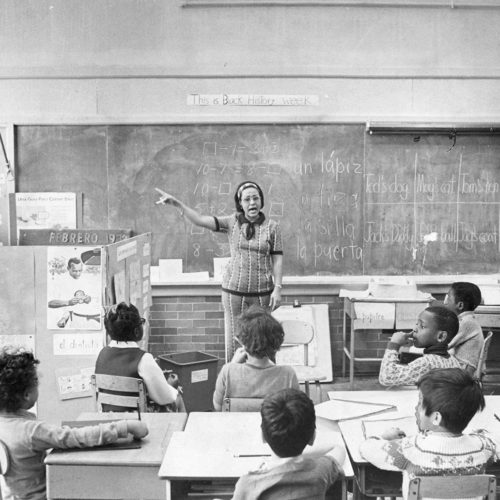

En 1970, para apoyar al creciente número de estudiantes de habla hispana, DCPS creó un programa experimental para las escuelas en las comunidades de habla hispana, donde estaban incluidas Oyster Adams, Eaton, Bancroft, Hearst y Cooke. El dinero para apoyar el programa provino de subvenciones del gobierno federal, DCPS, y fundaciones privadas. Se compraron materiales de lectura en español y se contrató y capacitó a profesores auxiliares, muchos de los cuales eran maestros acreditados en sus países de origen. Las familias de habla hispana podían decidir qué clases recibían sus hijos en español. Aunque el programa bilingüe de Oyster era reconocido como uno de los más sólidos, el director se opuso cortésmente a este programa. Sin embargo, los padres querían que sus hijos continuaran con educación bilingüe, aun cuando el experimento se desvanecía en otras escuelas.

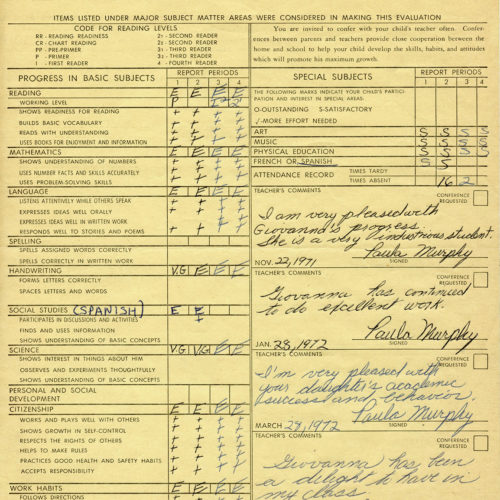

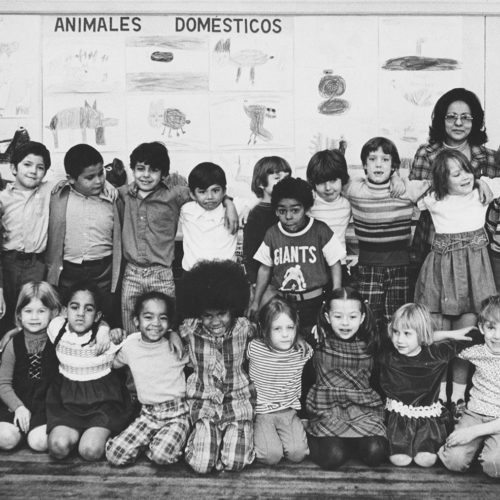

During the 1971-72 school year, there were eight or nine Spanish-speaking teachers and 70 Spanish-speaking volunteers at Oyster. Of the 295 students, 134 spoke Spanish, 117 spoke English, and 44 spoke one of 17 other languages. Spanish-speakers had 1/3 of their classes in English, and English-speakers had 1/3 of their classes in Spanish. Most subjects were available in either English or Spanish, but parents could choose to have their children take all classes in English.

Voices from the Oyster Community

”Tenía 23 años y estaba saliendo con el que me casé. Vino primero y luego me dijo que viniera... la forma de vida aquí era mucho mejor. Luego compramos una casa en Mt. Pleasant... Me encanta Washington, DC. Es maravilloso.

Maria Artiga, 2019Alumni Parent and Grandparent

”Mis padres se mudaron aquí muy jóvenes…como muchos salvadoreños, tuvieron que venir por la guerra civil…They were fleeing…it was a civil war that lasted many years and a lot of people died. Unfortunately a lot of them were bystanders.

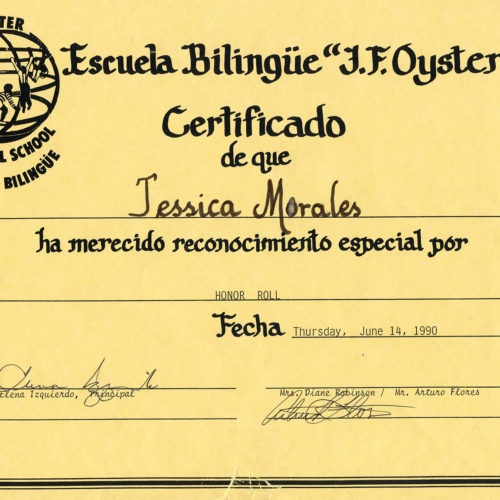

Jessica Morales, 2019Oyster Alumna

”Atencion! Un mensaje urgente para la comunidad Hispana. Se esta ofreciendo por primera vez en las escuelas publicas de Washington ,

D.C. Public Schools Announcement, 1970From The Washington Post

DC, un gran programa bilingüe para las escuela primaria desde kinder hasta sexto grado.

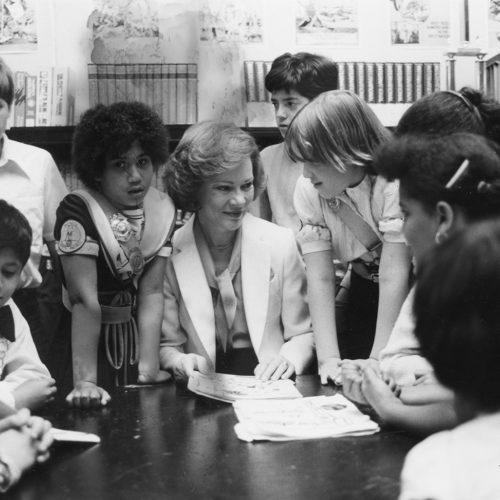

”…we want to give [Spanish-speaking] children a chance to learn about their own culture, to feel good about their language and where they came from. If we reinforce their native culture, we give them a feeling of self worth with which they’ll be able to function successfully in the educational process in the United States.

Mary Lela Sherburne, 1971From The Washington Post

”Spanish is a great world language. Why knock it out of children when we spend a billion dollars a year to train adults to be bilingual?

Dr. Gaarder, 1971From The Washington Post

”Most of [the students] are doing well. A few of them have decided that they can’t speak Spanish but some individual instruction will change that.

Miss Diana Sharp, 1971From The Washington Post

”I can talk to all my friends that are [Spanish-speaking]. Sometimes she [points to a friend] speaks Spanish to me and I don’t know what she is saying. Now I can understand her a bit.

Denise Jackson, 1971From The Washington Post

Escuela Bilingüe Oyster

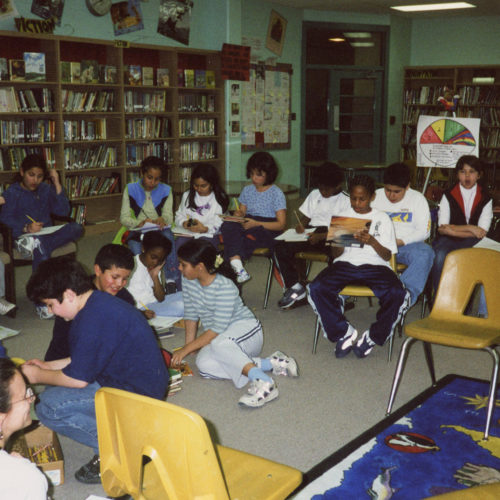

A diferencia de la mayoría de los padres en todo el país, los padres de Oyster querían que sus hijos asistieran a una verdadera escuela de dos idiomas. Buscaron el liderazgo de su nuevo director, Frank Miele. Cada salón de clases tendría dos maestros— uno nativo de habla inglesa y otro nativo de habla hispana. Independientemente de la asignatura, los alumnos aprendieron a responder en inglés o en español, según el profesor que estuviera en el pizarrón.

En la década de 1980, Oyster era una de las pocas escuelas bilingües del país. El Consejo de Padres ayudó a recaudar fondos para contratar maestros adicionales y comprar libros adicionales. Los hispanohablantes nativos constituían el 60% de la población estudiantil y la popularidad de la escuela se disparó. En 1983, a pesar del deterioro del edificio envejecido, la escuela tenía una lista de espera de más de 300 niños.

Voices from the Oyster Community

”[My dad] wanted me to go to my neighborhood school…he wanted me to learn another language and he knew the value of a bilingual education...

Andrew Miele, 2019Oyster Alumnus and Principal Miele’s son

”We were able to teach and we were able to experiment. [Principal Miele] was in charge and made things happen—but he also allowed things to happen.

Erasmo Garza, 2020

”The time it takes differs with each child. I had one boy who was speaking [English] fluently after two months. Most of the sixth graders now can read and have pretty good comprehension. Kids pick up a foreign language easily.

Henry Jackson, 1973From The Evening Star

”Oyster helped kids learn English but it also helped kids that spoke English to learn Spanish...We all had to rely on each other to figure things out...We weren’t stressed out—we had fun!

Connie Artiga-Oliver, 2019Oyster Alumna and Parent

”The school reinforces the Spanish-speaking students’ sense of pride and encourages them to use their native language while learning another. It provides a very positive reinforcement for students of both cultures to want to learn and use both languages.

Paquita Holland, 1977From The Evening Star

”We have to be practical. We’re running a bilingual school, and if a child doesn’t know the second language, we have to spend more

Frank Miele, 1980From The Washington Post

time on the language [they don’t] know…

”We start out in pre-kindergarten by talking to the children and teaching them English or Spanish just the way your mama taught you to talk…Later, we switch to more sophisticated stuff.

Marcello Fernandez, 1983From Education Week

”We didn’t want our children to forget their heritage. When we go back to El Salvador to visit now and then, our relatives are always happy to see that the children haven’t forgotten how to speak to them.

Horacio Artiga, 1983From Education Week

”I loved coming to school…Some of my friends spoke English at home and some spoke Spanish…it wasn’t until later that I realized how special that was and how not every school was like that.

Emma Arons, 2019Oyster Alumna and Parent

Surge la Escuela Bilingüe Oyster-Adams

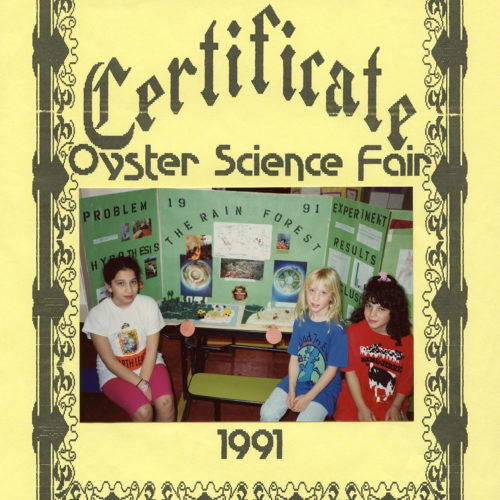

A principios de la década de 1990, se programó el cierre del deteriorado edificio de Oyster, muy deteriorado debido a la falta de financiación de la ciudad. Una vez más, los padres tomaron medidas y forjaron un acuerdo con el Fondo Escolar del Siglo 21 para salvar la escuela del barrio. A cambio de un nuevo edificio, Oyster le dió a un constructor casi la mitad de su propiedad (la mayor parte del área de juegos) para la construcción de un gran edificio de apartamentos. En 2001, los estudiantes de Oyster se mudaron a una escuela temporal, KC Lewis, durante tres años mientras se construía su nueva escuela.

In 2007, Oyster Bilingual School merged with John Quincy Adams Elementary School and a middle school was added to the bilingual program. Some Adams teachers feared the bilingual program would not be appropriate for their diverse student population, which included many children who did not speak either English or Spanish. Oyster was concerned that the merge would not preserve their bilingual roots. These fears proved to be unfounded.

Oyster-Adams continuó ampliando su programa educativo en varios idiomas. En 2007, se agregó el chino como un programa de enriquecimiento a la escuela secundaria. La inmersión en español se introdujo en prejardín en 2018 y en jardín en 2019. El programa de chino creció y en 2019 se ofreció a los alumnos de cuarto y quinto grado. Un año después, se expandió a todos los grados de la escuela secundaria.

Today, Oyster-Adams Bilingual School’s mission is to create an inclusive community of learners dedicated to academic excellence and creativity that develops globally responsible leaders who are bilingual and bi-literate in Spanish and English. Each bilingual classroom continues to provide two teachers, and enrollment is kept at an 50/50 split of English and Spanish native speakers.

”As a student at Oyster, I had the privilege of seeing the community thrive in three distinct buildings—the original building, the temporary building at KC Lewis, and the [current] building. I spent the majority of my Oyster education at KC Lewis. I remember carpooling, my friends, exploring the open space of the building, the baseball field, and the double playground…I look back at those days in awe of how the spirit of Oyster continued and grew…those years at KC Lewis best represented Oyster’s commitment to our most hallowed traditions

Aaron Bland, 2021Oyster Class of 2002

of diversity and inclusion.

”Los beneficios de los programas de inmersión son realmente innumerables. He tenido el honor de ser maestra de cientos de alumnos y conocer a familias de todo el mundo, lo cual trae una verdadera riqueza a la comunidad. He visto como TODOS los estudiantes se

Ana López, 2021Oyster-Adams Bilingual School teacher

benefician del programa.

”Bilingualism is the heart of Oyster-Adams. All our students are valued, challenged, and supported by it. It is their gateway

Mike Benson, 2021Oyster-Adams Bilingual School teacher

to a profound education.

”I’m proud to have served as principal of Oyster-Adams Bilingual School. A place where our students are taught to be bold, brave, and bilingual. At Oyster-Adams we empower our students to use their bilingualism to take pride in themselves and empathize with those who are different in order to change the inequities in our world. Our students see difference as a way to build a bridge, not a wall.

Mayra Cruz, 2021Oyster-Adams Bilingual School past principal

”…you get to have this amazing experience of knowing two languages [at Oyster-Adams], and you don’t have to look up [translations] on your phone—you can just know. I don’t think I’ve ever been in a school with so much history.

Elise Kaplan, 2020Oyster-Adams Bilingual School student

”Los beneficios de una escuela bilingüe son que puedes aprender dos idiomas a la vez (aunque uno de ellos no sea el tuyo). Otro beneficio es que al ser una escuela pública, más niños pueden beneficiarse del bilingüismo.

Blanca Pérez García, 2020Oyster-Adams Bilingual School student

”Un beneficio de asistir a una escuela bilingüe es que en el futuro te ofrece más opciones sobre trabajos y ademas con el conocimiento de un idioma puedes comunicarte con personas. [Lo] que me gusta de Oyster-Adams es que la comunidad también te ayuda donde lo necesitas. Otra cosa que también me gusta de Oyster Adams es que cuando un estudiante crece hace muchos recuerdos y amigos…

Gerber Martinez-Velasquez, 2020Oyster-Adams Bilingual School student

The Exhibit

The Story of Our Schools would like to thank the following organizations and businesses for their generous grants and donations:

Platinum Level

Oyster-Adams Bilingual School OCC | TPA Alumni Grant Challenge | Penn Hill Group | Alex & Maryam Nock | Danica Petroshius & Greg Whitsell | Claudia & Bill Anderson | Marvic Pak & Family | Nicolette & Tom Winkler

Gold Level

In the Memory of Lee Benson | Stephanie & David Deutsch | Anonymous | In the Memory of Alice Elizabeth Pountney-Dei

Silver Level

Sherry’s Wine & Spirits | Kalorama Pharmacy | Christina Morado | Jaime Crowe | Ivan Andre & Jean Daniel Morales | Joseph Kochan | Allan Woods Florist | McIntyre’s Pub | Erika Paro | George Cannon | John Morton & Tamar Shapiro | Manhattan Market | The Montes-Becker Family | Armandine Longang | Betty-Chia Karro | Dorothy Sheldon

Every school has a story to tell.

Are you ready to explore the story of your school?

Contact us to learn more about bringing Story of Our Schools to your neighborhood or make your tax-deductible contribution today.